Interview with Robin Peguero

Robin Peguero

author of "Without Prejudice"

Michael Carter

Co-Host

Robin Peguero, author of "Without Prejudice"

Robin Peguero's Website

After graduating from Harvard College and Harvard Law, Robin Peguero spent seven years telling stories to juries, most recently as a Miami homicide prosecutor. Currently he works for the U.S. House of Representatives as investigative counsel on domestic terrorism.

While a Miami Homicide prosecutor, he saw first hand that the criminal justice system should carry the same disclaimer as drug commercials: Results may vary.

Peguero goes on the say, “The hardest part in sitting across from accused killers in court – wagging my finger and turning my voice cold before the jury – was I didn’t often get to see regret. Only defiance. That was by design.

The adversarial system isn’t much built on concession. Even cases that close in plea deals might be subject to future appeals, and the less you say, the better. My curiosity in redemption was selfish. I wanted to better understand these life-takers for my own solace. I wanted see their humanity. I never doubted it was there. I just wished I were privy to seeing more of it. Trial is a battle of wills between two overeducated, self-important avatars, and the defendant – let alone the victim, whose life details go unmentioned – fades into the background.

He sadly becomes just another piece of furniture. As if his liberty doesn’t hang in the balance. After a guilty verdict, I made a habit of passing by the newly convicted on my way out and wishing him well. It was always brief, sometimes so under my breath that I couldn’t be sure they caught it all. If it was too showy, my words might come off mockingly when I meant to be earnest. But I did it mostly for me. I had just spent days talking about him, talking at him, but never talking to him. I wanted to form some sort of human connection, albeit fleeting. I wanted to see some part of myself in him.

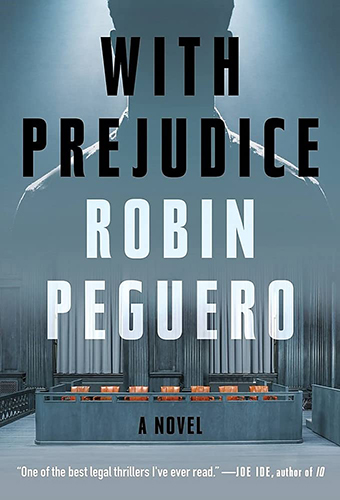

Robin Peguero’s penetrating legal thriller begins with seven strangers in a jury deliberation room, preparing to decide a man’s fate. By the end of the first chapter, it’s clear these people are far from being unbiased, for every single person has come to the table–as the title says–With Prejudice.

The story then shifts to introduce an ambitious young prosecutor named Sandy Grunwald, who’s preparing to start the murder trial of Gabriel Soto, accused of killing a young woman named Melina Mora two years ago. An eyewitness claims Soto was arguing with Mora at a bar earlier in the evening on which she disappeared, though the witness originally described the suspect as being of an ethnicity different from Soto’s. Mora’s body was never found, only a set of bones in a morgue that were identified as hers. The night before the trial begins, Grunwald receives a stunning blow to her case.

Gleefully lapping up this development is Grunwald’s formidable opponent, public defender Jordan Whipple. His rejection from all the Ivy law schools has become “a chip he carries on his overdeveloped shoulders.” Whipple will do whatever it takes to win, including going against his client’s wishes to paint a false picture of Soto in court.

Back in the deliberation room, readers get to know the diverse group of jurors: a white man who considers himself the enforcer of rules in his neighborhood; a Black tax collector who follows rules even though sometimes they work against him; a white progressive lawyer engaged in social justice for marginalized people; a Nicaraguan American doctor who’s not against fudging facts when the truth is too painful to reveal. These are some of the people sitting in judgment of the defendant, but are they truly his peers?

With Prejudice, Peguero’s first novel, delivers more than just a complex mystery; it pulls back the curtain to provide a 360-degree view of the American legal system’s inner workings. Besides delving into the backgrounds of the prosecutor, public defender and jury members, Peguero also serves up personal histories for the judge and the lead detective on the witness stand. Most of the key players show up with good intentions, but when everyone’s world views have been shaped by drastically different life experiences, it’s hard to agree on what’s right.

Peguero’s writing is striking for the stark observations about the legal system, such as this description from Grunwald, the prosecutor: “The jury is a crew of misfits. The scraps that neither side particularly wanted…. You don’t pick a jury. You’re left with a jury. If you’re too informed… then you might know too much. The court itself kicks you off. If you’re too opinionated… then you might think for yourself too much. It’s a race to the bottom.” Such a pronouncement might seem cynical, but it’s hard to argue that it doesn’t ring true.

The author also doesn’t pull punches when it comes to the goals of the attorneys on both sides. Instead of aiming for truth and justice, Grunwald and Whipple are more concerned about who will put on the best performance in the courtroom. At one point Whipple asks Grunwald, “How does it make you feel that you’re about to spend day after day pummeling a poor closeted gay kid in order to earn a conviction?” Grunwald snaps back, “The same way, I assume, you’ll feel about portraying a poor dead girl as a reckless, drunk whore who brought this all on herself.” As if these statements aren’t startling enough, both Grunwald and Whipple believe they have the moral high ground. The novel makes one ponder: Will either side’s actions deliver justice for the victim and reveal the truth about what happened to her?

While some of the characters have noble goals and others have questionable motives, none are portrayed as stereotypes. A good cop can still have shameful secrets from his past, and a doctor who heals patients can hide the harm and violence in her own family. Peguero shows the reasons that compel some people to move in gray areas, and how sometimes, regardless of intention, the consequences can be devastating.

As the omniscient narrative flits from person to person, it also travels back to when some of the characters were younger. Peguero cleverly depicts points in time without giving specific dates, years or even decades. Instead, he mentions someone buying VHS workout videos, or two young friends–one white, one Black–being called Riggs and Murtaugh, a reference to the characters in the 1980s Lethal Weapon movies. The absence of clear time markers helps stories move smoothly between time periods, and sharp-eyed readers won’t have a problem determining in what year a scene is set.

No matter the year, Peguero’s debut novel is a timely one, asking hard questions and revealing harder realities about an imperfect system. But for fans of legal thrillers, objectivity isn’t necessary. The verdict is that With Prejudice is a thought-provoking and satisfying read.