Interview with David Quammen and John Turner

David Quammen

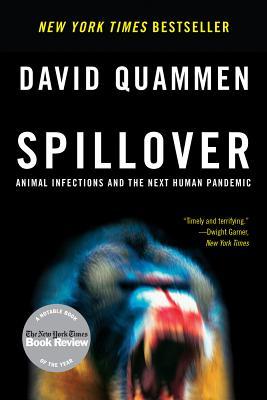

author of "Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic"

John Turner

author of "Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet"

Steve Murphy

Executive Producer & Host

David Quammen, author of "Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic"

David Quammen's Website

David Quammen (born February 1948) is a science, nature and travel writer whose work has appeared in publications such as National Geographic, Outside, Harper’s, Rolling Stone, and the New York Times Book Review. He wrote a column, called “Natural Acts”, for Outside magazine for fifteen years. Quammen lives in Bozeman, Montana. .

“Science writing as detective story at its best.” ―Jennifer Ouellette, Scientific American

A New York Times Notable Book of the Year, a Scientific American Best Book of the Year, and a Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Ebola, SARS, Hendra, AIDS, and countless other deadly viruses all have one thing in common: the bugs that transmit these diseases all originate in wild animals and pass to humans by a process called spillover. In this gripping account, David Quammen takes the reader along on this astonishing quest to learn how, where from, and why these diseases emerge and asks the terrifying question: What might the next big one be?

John Turner, author of "Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet"

John Turner's Website

I teach religious studies at George Mason University. My writing revolves around the place of religion in American history, a subject rarely free from controversy and often full of color. My first book, Bill Bright and Campus Crusade for Christ: The Renewal of Evangelicalism in Postwar America, won Christianity Today’s 2009 prize for best History / Biography. For those unfamiliar, Campus Crusade (which recently shortened its name to “Cru”) is one of the nation’s largest nondenominational evangelical agencies and is often the leading evangelical presence at public universities.

My scholarly journey from post-1945 evangelicalism to mid-nineteenth-century Mormonism was both challenging and exhilarating. I had considered writing a study of the Latter-day Saints and conservative politics since 1945, but as I began examining the history of Mormonism, I found myself pulled toward the earlier time period. The result is Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet, published in September 2012 by Harvard University Press. My portrait of Young emphasizes his early religious experiences (such as speaking in tongues), the transformative effect of Joseph Smith’s murder on Young’s personality and approach to leadership, Young’s outsized family, and his thirty-year battle with the U.S. government for control of the Utah Territory. My years with the Latter-day Saints have, in a roundabout way, returned me to my roots. I grew up outside of Rochester, New York (not terribly far from where Brigham Young worked as a craftsmen) and occasionally heard about Joseph Smith and Palmyra. Until I went to graduate school at Notre Dame, however, I don’t think I had met a single Mormon. Since then, I’ve seen the Hill Cumorah Pageant, visited Joseph Smith’s Farm and the Sacred Grove, and dragged my family to Mormon history sites from Utah to Vermont (complete Mormon Trail vacation yet to be funded and planned).

My shorter essays on Mormonism past and present have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times.

Brigham Young was a rough-hewn craftsman from New York whose impoverished and obscure life was electrified by the Mormon faith. He trudged around the United States and England to gain converts for Mormonism, spoke in spiritual tongues, married more than fifty women, and eventually transformed a barren desert into his vision of the Kingdom of God. While previous accounts of his life have been distorted by hagiography or polemical expose, John Turner provides a fully realized portrait of a colossal figure in American religion, politics, and westward expansion.

After the 1844 murder of Mormon founder Joseph Smith, Young gathered those Latter-day Saints who would follow him and led them over the Rocky Mountains. In Utah, he styled himself after the patriarchs, judges, and prophets of ancient Israel. As charismatic as he was autocratic, he was viewed by his followers as an indispensable protector and by his opponents as a theocratic, treasonous heretic.

Under his fiery tutelage, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints defended plural marriage, restricted the place of African Americans within the church, fought the U.S. Army in 1857, and obstructed federal efforts to prosecute perpetrators of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. At the same time, Young’s tenacity and faith brought tens of thousands of Mormons to the American West, imbued their everyday lives with sacred purpose, and sustained his church against adversity. Turner reveals the complexity of this spiritual prophet, whose commitment made a deep imprint on his church and the American Mountain West.”